Original Black Mozart – Chevalier de Saint-George Joseph Boulogne

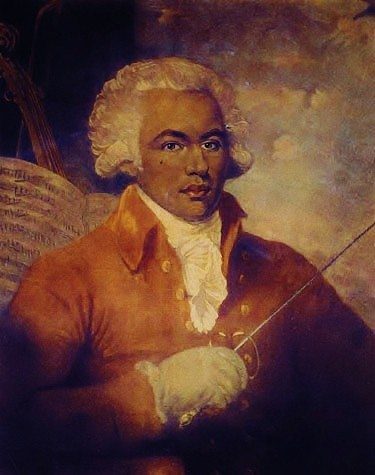

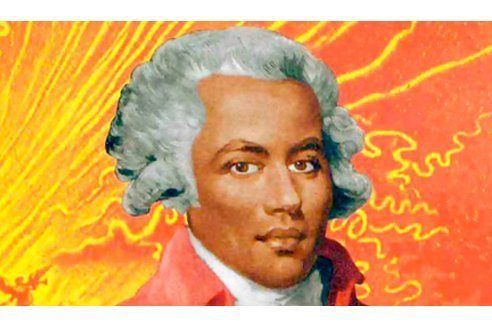

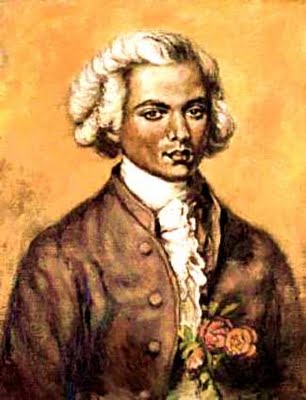

Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-George (1745–1799), a musician, athlete, and soldier, was among the most fascinating figures during the years at the end of France’s old regime and during its age of revolution at the end of the eighteenth century.

Long before the word “Super Star” was coined, Saint-George was the original. Many people throughout history have been famous for one reason or another. Many have made great contributions to civilization and left great legacies. Their paintings and sculptures we still admire. Their discoveries have made our lives better; their music we still play and sing, but no one in history was as talented in so many areas as Saint-George. For a time, he was the greatest fencer in the world. He was an exceptional violinist and along with his teacher, Gossec, he pioneered the composition of the String Quartet. Even Mozart came to Paris to study this new form of music. Saint-George was an unequaled equestrian, an exceptional marksman and an elegant dancer. The wealthy copied the way he dressed, and the common people admired him as he walked through the streets, and whispered his name. He was a true Renaissance man and a “super star” in the Paris of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Long before the word “Super Star” was coined, Saint-George was the original. Many people throughout history have been famous for one reason or another. Many have made great contributions to civilization and left great legacies. Their paintings and sculptures we still admire. Their discoveries have made our lives better; their music we still play and sing, but no one in history was as talented in so many areas as Saint-George. For a time, he was the greatest fencer in the world. He was an exceptional violinist and along with his teacher, Gossec, he pioneered the composition of the String Quartet. Even Mozart came to Paris to study this new form of music. Saint-George was an unequaled equestrian, an exceptional marksman and an elegant dancer. The wealthy copied the way he dressed, and the common people admired him as he walked through the streets, and whispered his name. He was a true Renaissance man and a “super star” in the Paris of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Saint-George is known today as one of the major early contributors of African descent in the tradition of European classical music. He gained fame as a violinist, conductor, and composer; some of Europe’s top composers created violin works with Saint-George in mind as the soloist, and he led the premieres of some of Franz Joseph Haydn’s greatest symphonies. The music of Saint-George himself, long forgotten, has been successfully revived. In his own time, however, Saint-George was known for much more than music. A champion fencer as a young man, he was the object of often veiled and sometimes overt racial controversy. He survived two assassination attempts. In his later years he abandoned the aristocratic world of his upbringing to fight for revolutionary ideals, and he was an early supporter of racial equality in France and England.

Product of Extramarital Liaison

Saint-George was born on the French-ruled Caribbean island of Guadeloupe on December 25, 1745. His last name has sometimes been spelled “Saint-Georges,” but his father generally dropped the final “s,” and a street named after the younger Saint-George in Paris also omits it. Saint-George’s father, George de Bologne Saint-George, was a plantation owner and slaveholder on Guadeloupe who while still in France had been part of the inner circle of King Louis XV. He was married and had a legitimate daughter, but he also had a slave mistress, likely born in Senegal, named Nanon and said to be exceptionally beautiful. It was unorthodox for George de Bologne Saint-George to acknowledge this interracial infidelity, and more unusual still when he took not only his wife but his mistress and illegitimate son with him to France in 1748, fleeing a court conviction for killing a man in a duel. Joseph Boulogne, as a man who was half black, was barred from French noble status but did enjoy his father’s support and patronage.

Saint-George received the tutoring appropriate for a young member of the French nobility, attending a boarding school run by a famous swordsman named La Boëssière. Besides fencing and swordsmanship, his studies included literature, the sciences, and horseback riding. The teacher became the first of several observers to write admiringly of Saint-George’s prowess with the sword. Saint-George was tall, handsome, and gracious, and he quickly found his way into the halls of the French aristocracy. In 1765 a fencer named Picard insulted Saint-George and challenged him to a duel. Saint-George at first refused, but his father promised him a new carriage if he fought and won. At the duel in the city of Rouen, Saint-George quickly emerged the victor. He suffered his first defeat the following year at the hands of the famed Italian fencer Giuseppe Gianfaldoni, who praised Saint-George and said that he would soon be the best fencer on the European continent.

In music, too, Saint-George was a standout student. Several of France’s leading composers had benefited from the elder Saint-George’s patronage in the past, and young Saint-George benefited from their musical attentions. He is thought to have studied the violin with one of the great French virtuosi, Jean-Marie Leclair the Elder, and he mastered the harpsichord (an ancestor of the piano) as well. By the late 1760s he had become the recipient of a dedication from François-Joseph Gossec, the composer at the center of Parisian concert life. In 1769 Saint-George joined an orchestra called Le Concert des Amateurs, directed by Gossec, as first violinist, and in 1773, when Gossec moved on to a different conducting post, Saint-George became the group’s director.

In music, too, Saint-George was a standout student. Several of France’s leading composers had benefited from the elder Saint-George’s patronage in the past, and young Saint-George benefited from their musical attentions. He is thought to have studied the violin with one of the great French virtuosi, Jean-Marie Leclair the Elder, and he mastered the harpsichord (an ancestor of the piano) as well. By the late 1760s he had become the recipient of a dedication from François-Joseph Gossec, the composer at the center of Parisian concert life. In 1769 Saint-George joined an orchestra called Le Concert des Amateurs, directed by Gossec, as first violinist, and in 1773, when Gossec moved on to a different conducting post, Saint-George became the group’s director.

Even as he notched these successes, Saint-George’s status in French society was an ambivalent one. Religious leaders were agitating for the end of slavery, and King Louis XVI himself was opposed to the practice. But interracial marriages were forbidden (Saint-George was never able to marry), and belief in the genetic inferiority of Africans was widespread. As word of his athletic and musical exploits spread, Saint-George became famous. Word even reached America of how he could swim across the Seine River using only one arm or shoot at and hit a coin thrown into the air, and he was something of a fashion trendsetter as well. But there was always an undercurrent of racial controversy surrounding his reputation. Saint-George had powerful backers who appreciated his talents, including Queen Marie Antoinette (to whom he was unusually close). But when he was considered for the prestigious post of director of the Paris Opéra in 1775, two of the company’s leading sopranos objected and petitioned the Queen (according to a biography of Saint-George appearing on the Artaria publishing company website), asserting that “their honor and the delicacy of their conscience made it impossible for them to be subjected to the orders of a mulatto.”

Listen: Violin Concertos by Joseph Boulogne Chavalier de Saint Georges

Premiered Haydn Works

Nevertheless, Saint-George was a major star in Paris in the 1770s. By 1772 he had written several violin concertos (works for violin and orchestra) for his own use as a performer; lyrical pieces of ambitious dimensions, they reentered the classical concert repertoire at the end of the twentieth century. The concertos are not flashy showpieces but bespeak a performer with a smooth, velvety tone even at the highest reaches of the violin’s range. Saint-George also played chamber music (music for small ensembles), enthusiastically submerging his own talents in a group sound, and he and Gossec were among the first French composers to write music in an important new genre of Austrian origin—the string quartet.

Saint-George, though not prolific, wrote a modest body of music that showed an awareness of current trends generally, and was widely heard. Mozart based a passage in his ballet score Les petits riens (The Little Nothings) on one of Saint-George’s melodies. Saint-George wrote a concerto for harp and orchestra, several symphonies and operas, and several works in characteristically French genres: the symphonie concertante (for a small group of instruments with orchestra) and quartet concertante (for a mixed group of small instruments). He also composed several symphonies and operas, some of which have been lost. The music publisher Bailleux signed a six-year agreement with Saint-George giving him publication rights to the composer’s future violin concertos.

One of the most celebrated individuals in the French capital, Saint-George had various nicknames. One was “Le Mozart Noir,” or the Black Mozart; on concert posters advertising both Mozart’s music and that of Saint-George, the two often received equal billing. Another was Le Don Juan Noir, the Black Don Juan, but it is unclear whether this part of Saint-George’s reputation was exaggerated. What was clear was that he aroused resentment in some quarters. In 1779 Saint-George and a friend were attacked by six men while walking. The still agile Saint-George fought them off successfully, but an investigation into the attack was mysteriously squashed, with rumors circulating that the attackers were secret police from the court in Versailles, and that the reason for the attack was Saint-George’s closeness to Marie Antoinette, with whom he often played music.

After the disbanding of the Concert des Amateurs, Saint-George founded a new group called the Concert de la Loge Olympique in 1781. Working with an aristocratic patron, he arranged for the composition of and conducted the first performances in 1787 of the six “Paris Symphonies” of Franz Joseph Haydn, widely considered the greatest composer in Europe at the time (Mozart was better known to connoisseurs than to the general public). He was still flying high as a composer, writing the successful opera La fille-garçon (The Girl-Boy) and also an opera for children, Aline et Dupré ou le Marchand des marrons (Aline and Dupré or The Chestnut Seller). The extent of his fame was shown when he gave a fencing exhibition in England in 1787 against an opponent believed to be a woman, the Chevalière d’Éon (actually a male French diplomat dressed as a woman): the event was depicted in paintings that circulated all over Europe.

Joined Anti-Slavery Activist Group

In England, Saint-George became involved with the country’s growing anti-slavery movement, and he founded a similar French group called the Société des amis des noirs (Society of the Friends of Black People). Apparently these activities were irritating to British slave dealers; Saint-George was attacked once again by a group of five men armed with pistols in London, but once again escaped serious injury, using his stick as an impromptu sword. Although he had broken an Achilles tendon when he was 40, he was still a formidable swordsman. Saint-George became France’s first black Freemason, rising to 33rd-degree rank.

Much of the last decade of Saint-George’s life was shaped by the French Revolution and its aftermath. He sympathized with the revolution’s democratic aims, and, living in the city of Lille, he became a captain in the National Guard. With his strong connections to the deposed French court, however, he was also the object of suspicion among revolutionary leaders; in the 1790s he truncated his aristocratic name to Monsieur de Saint-George and later to simply George. As war broke out between France and the Austrian monarchy, Saint-George joined a group of black Frenchmen who hoped to form a new corps that would volunteer for the fighting. Saint-George became a colonel in the new force, and another measure of its fame was that it was popularly known as the Saint-George Legion, although its official name was different.

Much of the last decade of Saint-George’s life was shaped by the French Revolution and its aftermath. He sympathized with the revolution’s democratic aims, and, living in the city of Lille, he became a captain in the National Guard. With his strong connections to the deposed French court, however, he was also the object of suspicion among revolutionary leaders; in the 1790s he truncated his aristocratic name to Monsieur de Saint-George and later to simply George. As war broke out between France and the Austrian monarchy, Saint-George joined a group of black Frenchmen who hoped to form a new corps that would volunteer for the fighting. Saint-George became a colonel in the new force, and another measure of its fame was that it was popularly known as the Saint-George Legion, although its official name was different.

Saint-George and his regiment saw heavy action, and Saint-George claimed credit for victory over the Austrians at Lille. He also played a key role in foiling the so-called Treason of Dumouriez, a plot by a renegade French officer, General Dumouriez, to seize the city; Saint-George fooled the officer’s agent, a General Miaczinski, into thinking he would offer no resistance, but then had him arrested. Dumouriez was forced to flee the country. Saint-George was hailed as a hero, but the power struggles that engulfed the Revolutionary government soon affected him as well. One of the deputies in Saint-George’s black regiment, Alexandre Dumas (father of the famous French novelist of the same name), was an ally of the revolutionary leaderRobespierre and his Reign of Terror. He denounced Saint-George, charging him with corruption and financial mismanagement. Saint-George was imprisoned in 1793 but released a year later after Robespierre’s fall.

The last years of Saint-George’s life were not happy ones. He returned to the Caribbean for several years in the 1790s and was deeply disillusioned by the black-on-black warfare he witnessed on the island of Santo Domingo (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), as slave rebellions broke out and the French government sent troops, many of them former members of the Saint-George Legion, to quash them. Back in France he became the director of a new orchestra called Le Cercle de l’Harmonie (The Circle of Harmony), which performed at the Palais Royale, the former home of the Duke of Orléans. His fame was still such that the orchestra attracted large crowds that admired its precision and energy. Living alone, Saint-George contracted a bladder infection and died on June 10, 1799. Several commemorative editions of his music appeared. But soon new restrictions on blacks appeared across France’s empire; slavery, which had been abolished in 1794, was reimposed by Napoleon Bonaparte, and fighting deepened in the Caribbean between slave rebels and French troops. Saint-George and his music were removed from orchestra repertoires and essentially from the history books, not to be rediscovered for nearly 200 years.

Books

Banat, Gabriel, The Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Virtuoso of the Sword and the Bow , Pendragon, 2006.

Guédé, Alain, Monsieur de Saint-George: Virtuoso, Swordsman, Revolutionary, a Legendary Life Rediscovered , trans. Gilda M. Roberts, Picador, 2003.

Smidak, Emil F., Joseph Boulogne called Chevalier de Saint-Georges , Avenira, 1996.

Periodicals

Investor’s Business Daily , January 19, 2006.

Virginian Pilot (Norfolk, VA), August 5, 2004.

Online

“Le Chevalier de Saint-George,” AfriClassical.com, (January 28, 2007).

“The Historical Biography of Joseph Boulogne (Le Chevalier de Saint-George): The Remarkable Life of a Superman Revisited,” (January 28, 2007).

“Joseph Boulogne Chevalier de Saint-Georges,” All Music Guide , https://www.allmusic.com (January 28, 2007).

“Saint-Georges, Joseph Boulogne de,” Artaria Editions, (January 28, 2007).

Source: Notable Biographies