Mzansi | Sistas Reggae Compilation honoring South Africa Women’s Day – The 1956 Women’s March, Pretoria, 9 August

MzansiReggae has put together a compilation of the Sistas in Reggae.

Visit Official Website for MzansiReggae

The compilation hopes to highlight the contribution made by female artists and to provide a soundtrack for Womens Month and beyond. It is a celebration of female voices. An eclectic mix of soulful reggae afro sounds. It showcases Legendary Sistas, Soulful Sistas, Reggae Queens, Rude Gyals, Roots Daughters and Sista Souljahs and Poetic Souls. It includes tunes from days gone by, up to the latest tunes of the day and everything else in between.

Take a listen and be blessed with the sounds of Mzansi Reggae, compliments of the Sistas.

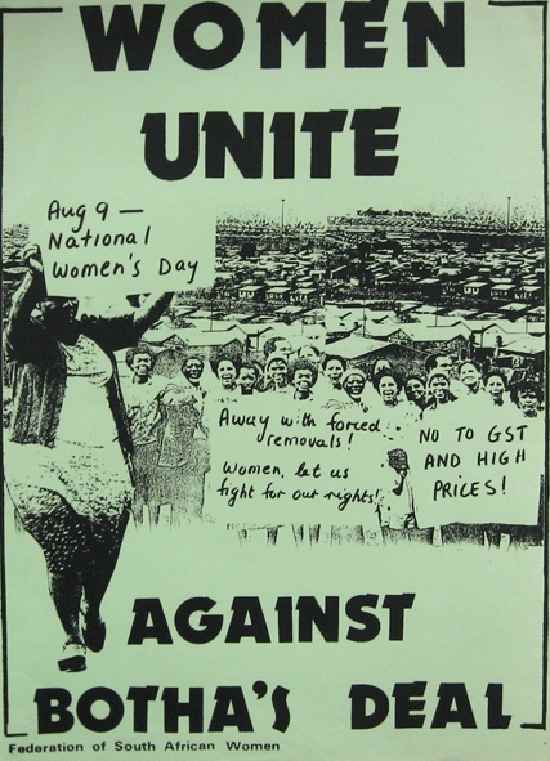

The turbulent 1950s – Women as defiant activists

‘Strijdom, you have tampered with the women,You have struck a rock.’So runs the song composed to mark this historic occasion

By the middle of 1956 plans had been laid for the Pretoria march and the FSAW had written to request that JG Strijdom, the current prime minister, meet with their leaders so they could present their point of view. The request was refused.

The ANC then sent Helen Joseph and Bertha Mashaba on a tour of the main urban areas, accompanied by Robert Resha of the ANC and Norman Levy of the Congress of Democrats (COD). The plan was to consult with local leaders who would then make arrangements to send delegates to the mass gathering in August.

The Women’s March was a spectacular success. Women from all parts of the country arrived in Pretoria, some from as far afield as Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. They then flocked to the Union Buildings in a determined yet orderly manner. Estimates of the number of women delegates ranged from 10 000 to 20 000, with FSAW claiming that it was the biggest demonstration yet held. They filled the entire amphitheatre in the bow of the graceful Herbert Baker building. Walker describes the impressive scene:

Many of the African women wore traditional dress, others wore the Congress colours, green, black and gold; Indian women were clothed in white saris. Many women had babies on their backs and some domestic workers brought their white employers’ children along with them. Throughout the demonstration the huge crowd displayed a discipline and dignity that was deeply impressive (Walker 1991:195).

Neither the prime minister or any of his senior staff was there to see the women, so as they had done the previous year, the leaders left the huge bundles of signed petitions outside JG Strijdom’s office door. It later transpired that they were removed before he bothered to look at them. Then at Lilian Ngoyi’s suggestion, a masterful tactic, the huge crowd stood in absolute silence for a full half hour. Before leaving (again in exemplary fashion) the women sang ‘Nkosi sikeleli Afrika’. Without exception, those who participated in the event described it as a moving and emotional experience. The FSAW declared that it was a ‘monumental achievement’.

The significance of the Women’s March must be analysed. Women had once again shown that the stereotype of women as politically inept and immature, tied to the home, was outdated and inaccurate. And as they had done the previous year, the Afrikaans press tried to give the impression that it was whites who had ‘run the show’. This was blatantly untrue. The FSAW and the Congress Alliance gained great prestige form the obvious success of the venture. The FSAW had come of age politically and could no longer be underrated as a recognised organisation – a remarkable achievement for a body that was barely 2 years old. The Alliance decided that 9 August would henceforth be celebrated as Women’s Day, and it is now, in the new South Africa, commemorated each year as a national holiday.

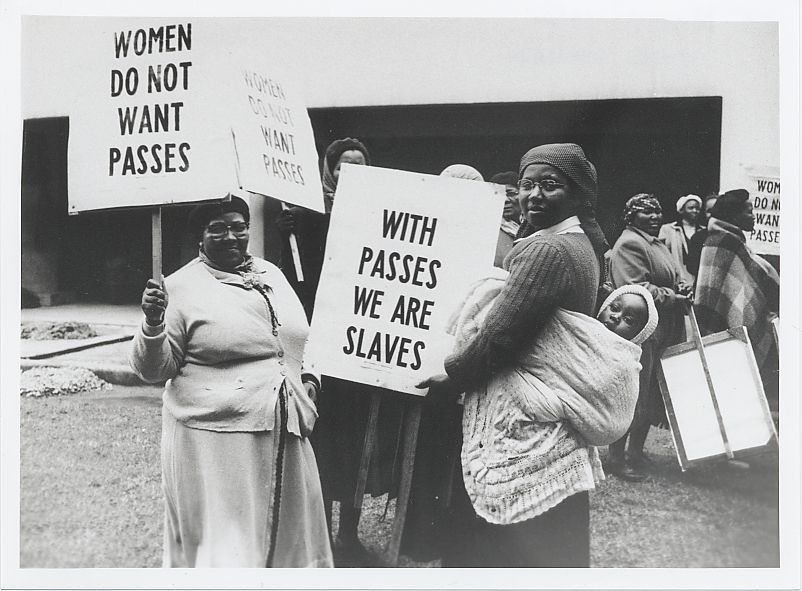

Passes for African Women

The Government`s first attempts to force women to carry passes and permits had been a major fiasco. In 1913, government officials in the Orange Free State declared that women living in the urban townships would be required to buy new entry permits each month. In response, the women sent deputations to the Government, collected thousands of signatures on petitions, and organised massive demonstrations to protest the permit requirement. Unrest spread throughout the province and hundreds of women were sent to prison. Civil disobedience and demonstrations continued sporadically for several years. Ultimately the permit requirement was withdrawn. No further attempts were made to require permits or passes for African women until the 1950s. Although laws requiring such documents were enacted in 1952, the Government did not begin issuing permits to women until 1954 and reference books until 1956. The issuing of permits began in the Western Cape, which the Government had designated a “Coloured preference area”. Within the boundaries established by the Government, no African workers could be hired unless the Department of Labour determined that Coloured workers were not available. Foreign Africans were to be removed from the area altogether. No new families would be allowed to enter, and women and children who did not qualify to remain would be sent back to the reserves. The entrance of the migrant labourers would henceforth be strictly controlled. Male heads of households, whose families had been endorsed out or prevented from entering the area, were housed with migrant workers in single-sex hostels. The availability of family accommodations was so limited that the number of units built lagged far behind the natural increase in population.

In order to enforce such drastic influx control measures, the Government needed a means of identifying women who had no legal right to remain in the Western Cape. According to the terms of the Native Laws Amendment Act, women with Section 10(1)(a), (b), or (c) status were not compelled to carry permits. Theoretically, only women in the Section 10(1)(d) category – that is, work-seekers or women with special permission to remain in the urban area – were required to possess such documents. In spite of their legal exemption, women with Section 10(1)(a), (b), and (c) rights were issued permits by local authorities which claimed that the documents were for their own protection. Any woman who could not prove her (a), (b), or (c) status was liable to arrest and deportation.

Soon after permits were issued to women in the Western Cape, local officials began to enforce the regulations throughout the Union. Reaction to the new system was swift and hostile. Even before the Western Cape was designated a “Coloured preference area”, Africans were preparing for the inevitable. On January 4, 1953, hundreds of African men and women assembled in the Langa township outside Cape Town to protest the impending application of the Native Laws Amendment Act. Delivering a fiery speech to the crowd Dora Tamana, a member of the ANC Women’s League and a founding member of the Federation of South African Women, declared:

We, women, will never carry these passes. This is something that touches my heart. I appeal to you young Africans to come forward and fight. These passes make the road even narrower for us. We have seen unemployment, lack of accommodation and families broken because of passes. We have seen it with our men. Who will look after our children when we go to jail for a small technical offence — not having a pass?

Source: SA History