Timkat: The Sacred Journey, celebrating the baptism of Christ in Ethiopia

In celebration of the baptism of Christ in the river Jordan, Timket is considered the most paramount festival of Orthodox Christians in Ethiopia. From the historical and spiritual aspect to the colorful processions and rhythmic hymns and celebrations, Antoine Lindley takes an insightful look at Ethiopia’s Timket “Epiphany” celebration and the deep heritage connection it has with Ethiopia and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Source: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Timkat (Amharic: ጥምቀት which means “baptism”) (also spelled Timket, or Timqat) is the Ethiopian Orthodox celebration of Epiphany. It is celebrated on January 19 (or 20 on Leap Year), corresponding to the 10th day of Terr following the Ethiopian calendar. Timket celebrates thebaptism of Jesus in the Jordan River. This festival is best known for its ritual reenactment of baptism (similar to such reenactments performed by numerous Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land when they visit the Jordan); early European visitors confused the activities with the actual sacramentof baptism, and erroneously used this as one example of alleged religious error, since traditional Christians believe in “one baptism for the remission of sins” (Nicene Creed).

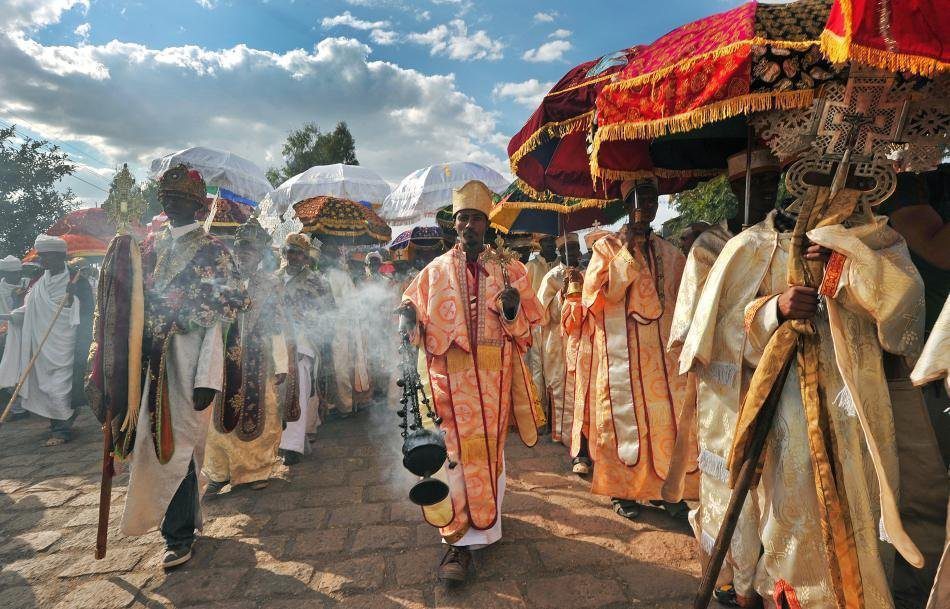

During the ceremonies of Timkat, the Tabot, a model of the Ark of the Covenant, which is present on every Ethiopian altar (somewhat like the Western altar stone), is reverently wrapped in rich cloth and borne in procession on the head of the priest.[1] The Tabot, which is otherwise rarely seen by the laity, represents the manifestation of Jesus as the Messiah when he came to the Jordan for baptism. The Divine Liturgy is celebrated near a stream or pool early in the morning (around 2 a.m.). Then the nearby body of water is blessed towards dawn and sprinkled on the participants, some of whom enter the water and immerse themselves, symbolically renewing their baptismal vows. But the festival does not end there; Donald Levine describes a typical celebration of the early 1960s:

By noon on Timqat Day a large crowd has assembled at the ritual site, those who went home for a little sleep having returned, and the holy ark is escorted back to its church in colorful procession. The clergy, bearing robes and umbrellas of many hues, perform rollicking dances and songs; the elders march solemnly with their weapons, attended by middle-ages men singing a long-drawn, low-pitched haaa hooo; and the children run about with sticks and games. Dressed up in their finest, the women chatter excitedly on their one real day of freedom in the year. The young braves leap up and down in spirited dances, tirelessly repeating rhythmic songs. When the holy ark has been safely restored to its dwelling-place, everyone goes home for feasting.[2]