If you know anything about Africa’s interactions with Europeans in the 1800s, you know that things didn’t go great for the Africans. Time and time again, a European “ally” nation would just happen to witness some malady befall one of their new African buddies. As a good neighbor, the Europeans would then prescribe their traditional folk remedy: military invasion. And so, time and time again, African armies would go up against European ones and lose.

But not in Ethiopia.

When its “ally” Italy began invading, Ethiopia defeated them in battle, and in so doing, made Italy collectively lose its mind. And this crushing victory? Due in large part to the foresight, skepticism, and unrelenting sass of one of the toughest women in Ethiopian history: Empress Taytu Betul.

this is an entry that has a shit-ton of extra info in the footnotes on the main site – so consider clicking here and reading the full thing)

Here Comes the Sun

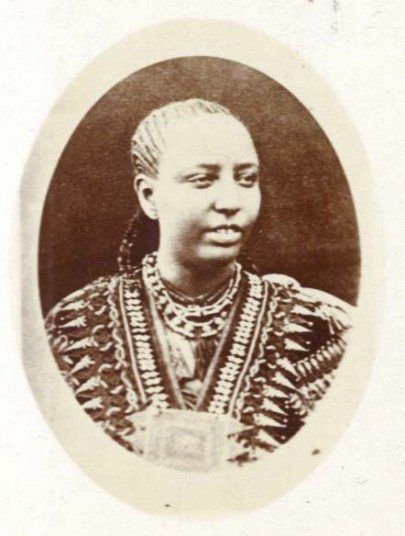

From the get-go, Taytu (Amharic for “sun”) was an odd choice for empress. As one of the Oromo people — a historically-downtrodden ethnic group in Ethiopia — Taytu was subjected to female genital mutilation before she was even three months old. This left her unable to bear children, one of the main expectations of any female royal. Moreover, before marrying emperor Menilek II, she’d had four husbands, and was over thirty years old (an eternity in Ethiopian marital terms).

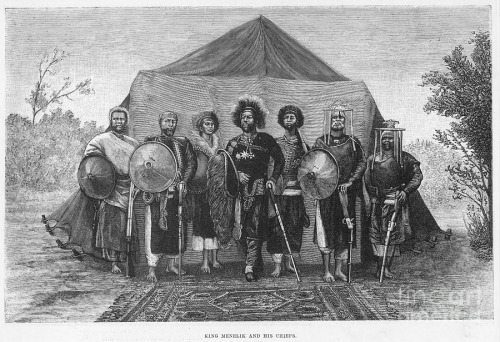

But they were a good match. Not only did her lineage give his reign legitimacy (she was linked to the Solomonic dynasties, a fact that overrode any concerns over her Oromo heritage), but she made him a more serious ruler by curtailing his womanizing ways. A popular song of the time played off Taytu’s name and that of Menilek’s hated mistress, saying “the sun [Taytu] has dissipated the fog [the mistress].” With Taytu’s help, Menilek gradually united the warring factions of Ethiopia under one banner.

The two settled into a well-polished good cop/bad cop routine. To avoid taking unpopular stances, Menilek II would straggle by saying “Ishi, nega,” (yes, tomorrow), while Taytu would decisively say “Imbi” (absolutely not). She became a savvy adviser to his every political move, interrupting negotiations “often in a decisive and resolutely hostile way.” She was one of the first to realize Italy’s intentions to make Ethiopia its thrall, and bluntly called Italy out on it: “You want other countries to see Ethiopia as your protege, but that will never be.”

By the time Italian-Ethiopian relations broke down in 1891, Italian diplomats came to describe Menilek as “weak, uncertain, and in the hands of his wife.” Which is to say, good hands.

“Victory is ours!”

After multiple attempts to sue for peace, Menilek and Taytu settled in to repel Italy’s immiment invasion. Taytu joined her husband on the front lines, traveling around with a personal force of 5,000 soldiers who, under her taskmaster guidance, “kept perfect order.” Witnessing the professionalism of her troops, a European observer wrote that Taytu “is a great lady, who perhaps in another milieu would have been a Christina of Sweden or a Catherine the Great.”

(White person code for “if she wasn’t black.”)

Taytu’s shining moment in the war came with the 1896 Siege of Mek’ele. Here, the Italians were holed up in a fortress, where they easily repelled Ethiopian assaults. Taytu took 900 of her men aside and instructed them to cut off the fort’s water supply. They did so, and after 10 days of increasingly horrific suffering, the Italians surrendered.

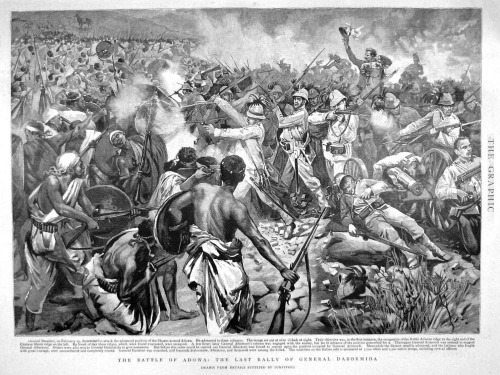

A month later, the war ended with the Battle of Adwa, where Italy suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of a united Ethopia. In multiple (likely exaggerated) histories of the battle, Taytu strode into the fighting herself. After seeing her soldiers beginning to lose heart, she dismounted, removed her veil, and yelled, “Courage! Victory is ours! Strike!” Some tellings even have the middle-aged woman armed to the teeth and plunging headlong into the fray. Which provided much fodder for earlier drafts of the above illustration.

“Who does she think she is? Empress Taytu?”

After the Italian defeat, the European nations, shocked at the Ethiopian victory, began negotiating in good faith — often with Taytu herself. When negotiating for the release of their prisoners of war, the Italians specifically asked to speak to Taytu. The Italian accounts of the time showed a country as divided as the United States after the Vietnam War, with some clamoring for revenge and others questioning why they’d even gone there in the first place. The Italian press took very polar stances on Taytu herself. While some compared her to Zenobia, Cleopatra, and Joan of Arc, others spun up hoary tales of how she bathed in blood, gossiped about her earlier marriages and purported side lovers, and began calling her a modern-day Jezebel.

To be fair, she was a divisive figure even among her people. On the one hand, she was capable of great mercy and societal progress: she personally cooked for prisoners and starving countrymen, inaugurated the Ethiopian Red Cross, founded the new capitol of Addis Ababa, and worked to kickstart many national industries, including wine production, candle-making, and more. In the words of one observer, she “applied herself not only to feminine works, but like quicksilver attended to perplexing business usually done by men, and succeeded at it.”

On the other hand, she could be a brutal politician and ruler. She filled the government with nepotistic political appointments in order to solidify her political base, especially as Menilek’s health declined. She was linked to a staggering number of poisonings, she persecuted those who spread foreign religions, and she was rude to the point of xenophobic with European envoys – although, given Ethiopia’s history with Italy, that last point is a bit more understandable.

Also, in the accounts of many Europeans, she grew fat. Not that it had anything to do with anything — but they felt the need to mention it. At length. Repeatedly.

When Menilek’s health took a plunge, Taytu became de facto ruler for a couple years — and it took the a massive conspiracy on the parts of much of the Ethiopian elite to oust her from power. When Menilek finally died, Taytu stepped down and lived a fairly quiet life until her death.

Her reputation lived on long past her death – both in Ethiopia, where she became a national heroine, and in Italy, where she was, for a time at least, the linguistic gold standard for a lofty woman. The once-popular phrase “Chi si crede di essere, la regina Taitù?” translates to “Who does she think she is? Empress Taytu?”

- Taytu is here depicted in a tent before the Siege of Mek’ele, playing chess with a European.

- She’s knocked over both his pieces and his glass of water — a callback to how she cut off the fort’s water supply.

- The European diplomat is standing up, soaked from having water tossed on him.

- She is, of course, holding up the queen. She was actually quite a chess player in real life.

- In the background, Menilek II is rallying the troops to take on the fort. Throughout, the crowd you can see tiny red umbrellas – these are parts of Taytu’s personal unit, which had a number of women in it, escorted by men shading them with red parasols.

- The man in the background is just a personal bodyguard, no real story there.

- The chair, table, tent layout, her clothing, and that of everyone else, is as period accurate as I could make it.

via: Rejected Princesses