Indian-Style: Natives and Black Folks in This Together Since 1492

I love being Native.

I literally had no choice. My beautiful full-blooded Blackfeet mom—the most beautiful woman in the world—taught me to love who I am. I also love being a quarter black—my mixed-breed dad, part black, white and Native—was strong and smart with amazing almond brown skin.

A powerful combination.

I literally didn’t realize I was a quarter black (actually a bit less than a quarter, but I’ll claim a quarter for easy math) until I was almost 13. My (almost) half-black dad really didn’t look stereotypically “black.” He looked Hispanic or maybe even Middle-Eastern—handsome dude with long wavy hair, brown skin and he had the coolest mustache. Hey, it was the 80s!

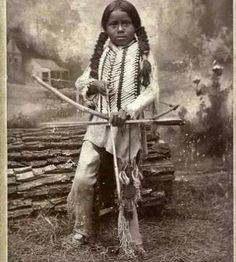

Growing up on the Blackfeet Reservation (and then later on the Nisqually and Suquamish Reservations, as well as urban areas), I was a dusty rez kid just like the other dusty rez kids. I didn’t really get treated differently or even know that I was part black—at least I never really noticed. I always identified as simply “Native” because I was raised by a full-blooded Native, single mom—but when I actually found out, I was overjoyed!! “Heck, that means I’m a little bit like Michael Jackson!!”

It was never really an issue.

In hindsight, I realize that I (probably fortunately) missed out on some of the complicated and ugly stuff that sometimes happens to Natives with black ancestry. Colonization is complicated, and in the same way that even black folks have been convinced that other black people are inherently dangerous—hence the disgusting amount of black-on-black crime—many Native people seemingly have bought that lie and sometimes given into ugly racist attitudes toward black folks (to wit, the Cherokee Nation with the Freedmen racism).

We also sometimes see examples of black folks buying into the ugly racism against Native people and we realize that we all buy into the racist bullsh*t. Even black folks. Even Native folks. None of us are exempt.

We’re all human.

For example, a friend of mine told me about his experience learning proper protocol for ceremony. He’s a young man, fluent in his Native language and consequently was being trained in being a leader in his people’s ceremonies. He was also, like many young people, a product of the hip-hop generation and dressed accordingly. One day, one of the older ceremonial men asked him, “Why do you dress like those black rapper guys?” My friend responded, “Should I dress like those white cowboy guys like you?”

And that’s precisely right. Natives oftentimes don’t question white people’s influence on Native culture—from the English language we speak to the white blood in many Natives. Most Natives don’t bat an eye when they see a Native person with light hair or light eyes or light skin—“that’s just a fair-skinned Native”; many of those Natives do,consciously or unconsciously, question the “Nativeness” a person when they have kinky hair or dark skin.

“Natives oftentimes don’t question white people’s influence on Native culture.”

It’s not our fault—all of us have been trained through 500 years of brainwashing, that light skin is “normal.” The dark skin is foreign to us even though, before colonization, Native people’s skin color was much closer to that dark skin than white skin. In the words of Chris Rock, “It’s alright because it’s all white.”

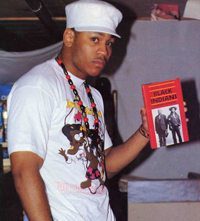

Hopefully that’s changing a bit. African-Americans dominate pop culture in America; they influence everyone. While some talk about non-Natives appropriating (I call it “being influenced by”) Native culture, we must also acknowledge the Natives who appropriate (“are influenced by”) black culture, as evidenced by the many Native hip-hop artists, fashion, etc. Everyone is influenced by someone, right? Nothing wrong with that. In fact, it’s positive—with every single Native kid who loves or emulates Jay-Z or Drake, it’s actually acknowledging a link that’s been present for centuries.

Let me explain.We’re gonna examine this history a bit. I will interview a couple of Natives with black ancestry and let them explain their own experiences and speak for themselves; I think you’ll enjoy. I’d like to leave you with this thought: the history, post-1492, of black folks and Native people are inextricably linked. Natives and African-Americans are forever profoundly connected on Turtle Island through blood, money and time, from the Triangle Trade to slavery. Specifically, when the white settlers first landed on this continent, they were looking for resources to exploit. Finding Turtle Island to be a land of plenty with cotton, sugar, and tobacco (the beginning of the Triangle Trade), the white settlers sought sources of labor. Native people, unfortunately, had very little immunity to the disgusting diseases the white settlers brought over from the Old World. Therefore, many Natives died very quickly and were not able/willing to be enslaved to the European interlopers. Hence, the “Middle Passage” route began which brought Africans from the West Coast of Africa to replace the rapidly dying Natives as the Source of Labor. Later, as those African slaves were shackled into brutal slavery, those who escaped the hands and whips of the slaveholders oftentimes sought/found refuge in our beautiful Native homelands, where territorial law enforcement was unwelcome.

Let me explain.We’re gonna examine this history a bit. I will interview a couple of Natives with black ancestry and let them explain their own experiences and speak for themselves; I think you’ll enjoy. I’d like to leave you with this thought: the history, post-1492, of black folks and Native people are inextricably linked. Natives and African-Americans are forever profoundly connected on Turtle Island through blood, money and time, from the Triangle Trade to slavery. Specifically, when the white settlers first landed on this continent, they were looking for resources to exploit. Finding Turtle Island to be a land of plenty with cotton, sugar, and tobacco (the beginning of the Triangle Trade), the white settlers sought sources of labor. Native people, unfortunately, had very little immunity to the disgusting diseases the white settlers brought over from the Old World. Therefore, many Natives died very quickly and were not able/willing to be enslaved to the European interlopers. Hence, the “Middle Passage” route began which brought Africans from the West Coast of Africa to replace the rapidly dying Natives as the Source of Labor. Later, as those African slaves were shackled into brutal slavery, those who escaped the hands and whips of the slaveholders oftentimes sought/found refuge in our beautiful Native homelands, where territorial law enforcement was unwelcome.

From that very early moment in history, there was much cultural, linguistic and biological mixing between Native and black lives and cultures.

In 2015, we still see those narratives intersect, with increasing scrutiny for the brutal pattern of law enforcement’s treatment within both of our communities. When we look close enough we realize that black folks’ and Natives’ history, conquest and ultimately, liberation is very closely related. As Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shore, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society.” In other words,we’re stuck with each other. Black folks know it too—that’s why so many of them are always excited to tell any Native person within earshot about their Native ancestry.

Together, we could be an incredibly powerful force if we’re just willing to look deeply enough.

Source: Indian Country Today Media Network

Source: Indian Country Today Media Network