How racist USA system is poisoning water in “Black” communities

RTV NOTE: We are publishing this article in hopes it will RING THE ALARM & SOUND THE TRUMPET for our people to start to ORGANIZE & CENTRALIZE to begin immediate relocation of all stolen Ethiopians/Afrikans captured and forced to live in subhuman conditions throughout the world and especially the western hemisphere.

Not only is the water poisoned in Flint, Michigan, we realize that the water supply is poisoned in many “Black” neighborhoods throughout Amerikkka. There are reports of brown water coming from faucets filled with lead, arsenic, filth and tetracholorethylene (PCE). Investing in a good water filter is no longer a luxury, it should be MANDATORY!

We visited the town of East Orange, New Jersey where residents were sent a letter from the East Orange Water Commission in the Fall of 2015 that their water hasdbeen poisoned since 2011 with tetracholorethylene (PCE) and they were just being notified in recent months. Not only did the City of East Orange admit that their water system violated a drinking water standard in 2011, but they also have TRIPLED the water rates since then. Some residents state that their water bill went from $150 per month to now $450 per month. After interviewing some local mothers, they claim their children have been complaining of stomach cramps, vomiting and lethargy. Here are some articles to back up our findings. This a perfect time for relocation and investing in self reliant projects, organic farming and water filters.

Why 11 N.J. cities have more lead-affected kids than Flint, Michigan

Eleven cities in New Jersey, and two counties, have a higher proportion of young children with dangerous lead levels than Flint, Mich., does, according to New Jersey and Michigan statistics cited by a community advocacy group.

With the eyes of the nation focused on the brain damage and other problems associated with lead-contaminated water in Flint, several community advocacy organizations in New Jersey banded together this week to draw attention to New Jersey’s lead problem, asking for a renewed focus on solving it.

In New Jersey, children 6 years of age and younger have continued to ingest lead from paint in windows, doors and other woodwork found in older homes, particularly in older, poorer cities, said Elyse Pivnick, director of environmental health for Isles, Inc., a community development organization based in Trenton.

“In light of the Flint debacle, we wanted people to understand that water is not the only thing that’s poisoning children,” she said. “Most people think the lead problem was solved when we took lead out of gasoline and new homes in the 1970s, but that’s not true.”

The communities with the high lead levels include Irvington, East Orange, Trenton, Newark, Paterson, Plainfield, Jersey City, Elizabeth, Atlantic City, New Brunswick and Passaic, along with Salem and Cumberland counties.

“You can breathe it in from dust and you can swallow it,” Pivnick said.

New Jersey Department of Health statistics from 2014, the last year for which data is available, show that those 11 cities and two counties had a higher percentage of children with elevated lead levels than Flint did in 2015, as shown by Michigan state statistics.

Also, Pivnick pointed out, in 2015, there were more than 3,000 new cases of children under the age of 6 in New Jersey with elevated levels of lead in their blood. Overall, advocates said, about 225,000 young children in the state have been afflicted by lead since 2000.

At a Trenton press conference on Monday, Isles Inc. and several other community action groups called on Gov. Chris Christie to restore $10 million in funding for the Lead Hazard Control Assistance Fund in the next state budget.

That money had been earmarked for the removal of lead from older homes, and also financed home inspections, emergency relocations for affected families and efforts to educate the public.

Just two weeks ago, Christie pocket-vetoed a $10 million bill that set aside money for the lead control assistance fund. This was the third consecutive two-year legislative session in which the bill failed to be signed into law.

The $10 million is money accrued based on a fee on paint sales, but governors have diverted the funds’ revenue to support the state budget since the fund was established in 2004, according to the bill’s supporters.

In addition to more state funding, Pivnick and the other advocates called for more involvement by local communities and leaders in focusing on the lead problem, including enforcing housing codes more diligently and expanding inspections to rental units with fewer than three bedrooms.

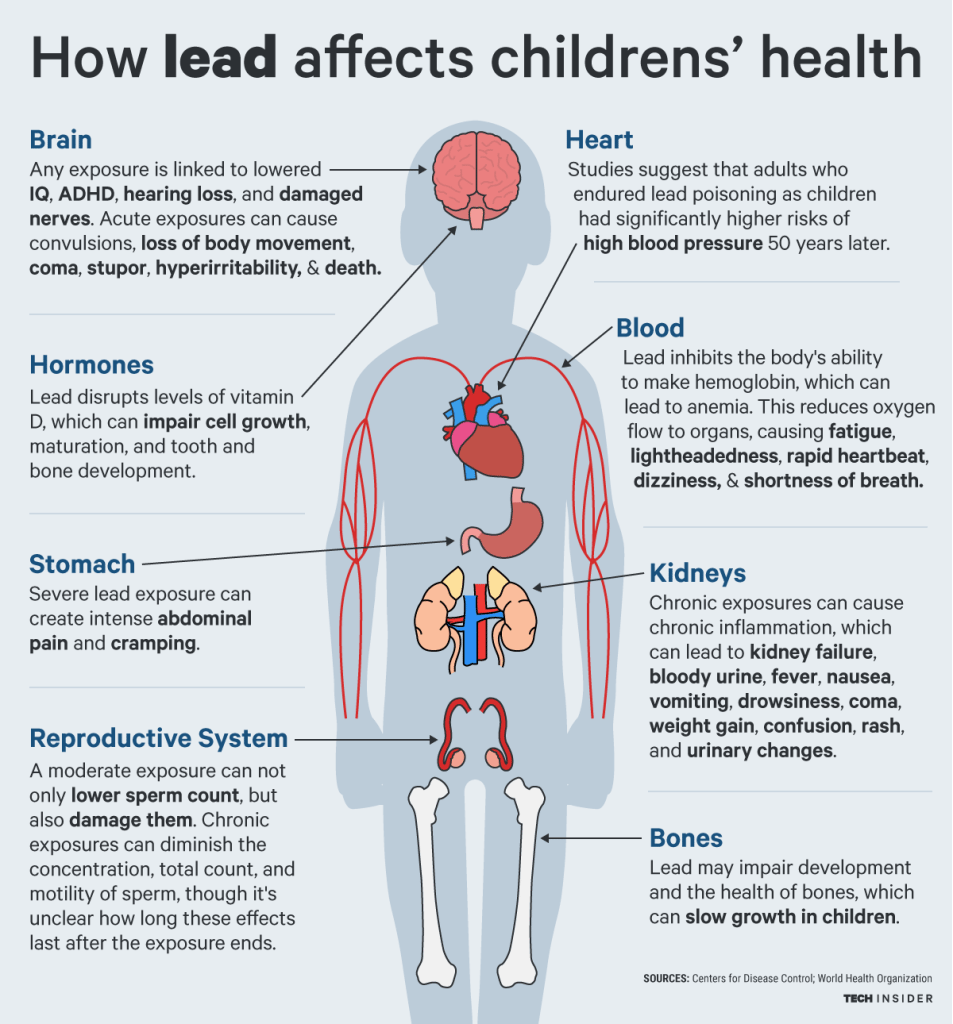

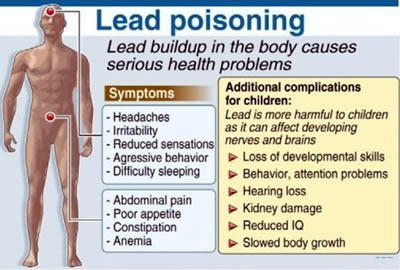

Lead poisoning leads to brain damage and the associated memory loss and related learning disabilities, and it “robs children of their potential,” Pivnick said.

With the problem even more widespread in New Jersey than it is in Flint, Pivnick said, “We should have the same protocols in place that Flint does. Why aren’t the same alarms going off here?”

Sen. Ronald Rice (D-Essex) agreed, “We’ve seen the national outrage resulting from lead-contaminated water distributed in Flint. We have our own crisis in New Jersey that cannot be ignored.”

Other groups joining the campaign included the Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey; New Jersey Citizen Action and the Anti-Poverty Network of New Jersey.

Responding for the state, Donna Leusner, a spokeswoman for the Department of Health, did not refute the statistics circulated by the advocacy groups, but pointed out that they are based on a “lower standard” for lead levels in blood than is currently in state regulations.

Over the past 20 years, Leusner said, the trend in the number of children with elevated lead levels has fallen significantly, while the number of children tested has increased significantly.

In the last fiscal year, she said, 205,607 children were tested for lead, compared with 10,200 in 1998. Also, she said, the number of children with elevated blood levels, based on the higher standard, dropped over the same period.

“The facts are that in New Jersey, childhood lead poisoning is a public health success story,” she said. She pointed out that New Jersey is one of just 17 states that have universal testing for children ages 1 and 2.

She pointed out that the Flint statistics were based on 2015, but a leading pediatrician there projected that the number of Flint children under 6 with elevated blood lead levels will reach 8,000 in 2016.

By comparison, she said, New Jersey’s officials statistics, based on its current standard, show 885 reported cases of elevated blood lead levels in children under 6 for 2015.

Tammori Petty, a spokeswoman for the Department of Community Affairs, added, “New Jersey is out ahead of the majority of states in that we continue to regularly and systematically inspect multi-family housing for lead-based paint hazards.”

Leusner said the health department “has no idea if data regarding Flint that advocates are citing is accurate or is being fully explained, particularly in comparison to other regions in the nation.”

Pivnick acknowledged that New Jersey is hardly the only state with a lead paint problem, but said the groups’ main purpose was to get more state funding to help solve the problem.

She said her group used the 5 mg/dL standard because it’s what the federal Centers for Disease Control uses. New Jersey uses a standard of 10 mg/dL (micrograms per deciliter).

CLICK HERE TO SEE THE CHART OF THE LEAD LEVELS IN NJ URBAN AREAS WHICH IN PLACES ARE MUCH HIGHER THAN FLINT MICHIGAN

Source: NJ.com

———————————————————————-

Your Take: When the citizens of Flint lost control of their government, emergency managers started pumping in filthy, lead-filled water, and the children of Flint are paying the price.

Tainted water is poisoning thousands of children in the predominantly African-American city of Flint, Mich. The high levels of lead in Flint’s water may create a plethora of serious, long-term health problems including brain damage, behavioral troubles, anemia and kidney problems.

On Wednesday, Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder declared a state of emergency in Flint and Genesee County in response to high levels of lead in Flint’s water supply. The U.S. attorney’s office has launched an investigation to understand who is responsible, and filmmaker Michael Moore has called for Snyder’s arrest. This investigation, however, must go beyond blaming one individual, because the current water crisis is a direct result of racialized state politics.

Flint’s citizens, 52 percent African American, have been deprived of the right to govern their city since 2011. Michigan’s Emergency Manager Law allows the governor to appoint an unelected official to control a city determined to be in fiscal crisis. Emergency financial managers have been primarily assigned to majority-African-American cities across Michigan. In the past decade, over half of African Americans in Michigan—compared with only 2 percent of whites—have lived under emergency management. EFMs are supposed to take over cities based on a neutral evaluation of financial circumstances—but majority-white municipalities with similar money problems have not been taken over. Flint’s poisoning is one effect of the systematic stripping of black civil rights in Michigan.

Flint’s water crisis began in 2014 when, to save money, Flint’s successively appointed EFMs, Ed Kurtz and Darnell Earley, switched the city’s water source to the Flint River rather than renewing the city’s water contract with Detroit—an established, safe water supplier. Residents immediately began complaining that brown water flowed from their faucets, yet health concerns were disregarded by officials, including Earley’s EFM successor, Gerald Ambrose.

As early as March 2015, officials knew that the water contained E. coli and carcinogens. By fall, it was revealed that residents’ drinking water contained high levels of lead and copper, contributing to significant reported health problems. Despite public assurances in July from Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality that concerned residents should “relax,” an external research team from Virginia Tech found lead levels were a staggering 16 times the allowed limit, and a local pediatrician found that lead poisoning had doubled among Flint children in a single year. (There are twice as many black children as white children in Flint.)

It took national media attention to make the state apologize and provide tap filters for residents. The city returned to getting water from Detroit in October 2015, but experts argue that the city’s infrastructure was damaged by the Flint River’s corrosive water. As a result, levels are still high, since corroded pipes may not be capable of preventing toxins from leaking into the water supply.

What gave this unelected person the power to poison a city? Emergency financial management, which grants virtually unlimited power to an unelected official, lies at the heart of this story.

The EFM law, as designed and implemented, rests on the premise that democracy in predominantly African-American cities is unnecessary and that the state knows best. But the state shares blame for Flint’s fiscal problems: It cut almost $55 million in expected revenue to Flint from 2003-2013 in a move that disproportionately defunded already impoverished (and majority-African American) cities.

Six EFMs have governed Flint in the past 13 years. Because budget deficits trump all other concerns, EFMs’ financial decisions have followed the austerity playbook, including cutting pay or firing unionized city employees and selling city properties. Cities under EFM have no one to hold accountable for the impact of these decisions—including decisions that result in poisoned water.

Water provides a telling window into the harmful effects of EFMs on African-American citizens. Various EFMs across Michigan, including Flint, have used water as a revenue stream by hiking fees,attempting to privatize systems or borrowing from the water budget. EFMs in Detroit and Highland Park have implemented draconian punishments for households unable to pay high water prices (including cementing over valves) while ignoring delinquent companies’ bills. And in Flint’s case, the deposed city government couldn’t independently check water quality after concerns were raised.

Flint’s poisoned water reveals the toxicity of the EFM law. Though several families filed a lawsuit against Earley and others, they areunlikely to succeed, since government agencies can’t be held liable for how they do their job.

Michigan’s EFM law deprives local residents of basic political rights. Because African Americans are more likely to live in cities with EFMs, they are more likely to be impacted by their decisions. We are left to wonder: Would this happen in a majority-white city? This law and its effects reveal unpleasant truths about race and democracy in 2016.

Source: The Root