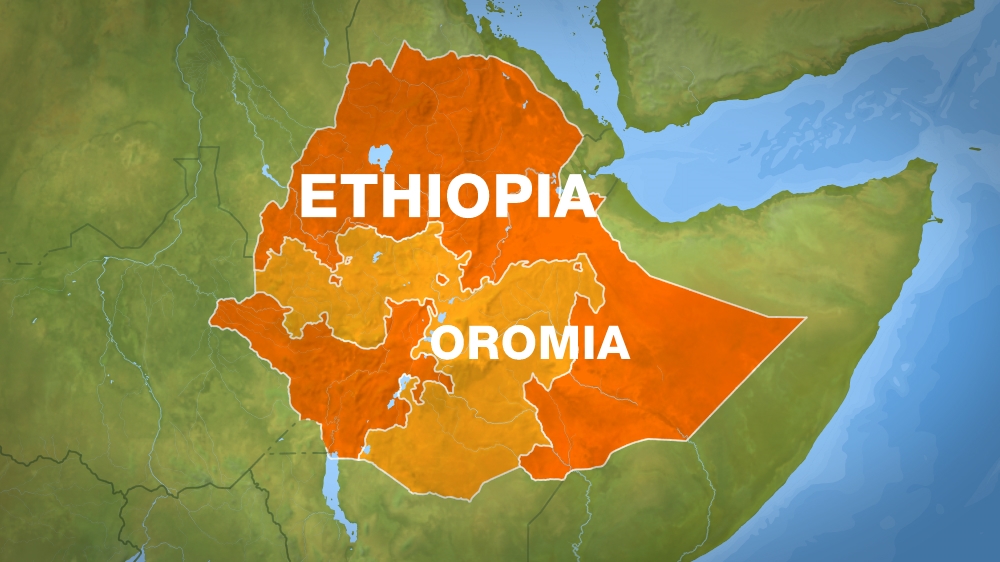

Ethiopia declares state of emergency over protests & unrest in Oromia region

Ethiopian Government declares a state of emergency effective immediately following violence and unrest in Oromia region.

Ethiopia has declared a state of emergency following months of often violent anti-government protests, especially in the restive Oromia region.

“A state of emergency has been declared because the situation posed a threat against the people of the country,” Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn said on state-run television on Sunday.

Local media said the state of emergency, declared for the first time in 25 years, will last for six months.

Demonstrators chant slogans while flashing the Oromo protest gesture during Irreecha, the thanksgiving festival of the Oromo people, in Bishoftu town, Oromia region, Ethiopia, October 2, 2016. REUTERS/Tiksa Negeri – RTSQF70

Earlier on Sunday, the state Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation reported that the state of emergency was effective as of Saturday evening as a means to “deal with anti-peace elements that have allied with foreign forces and are jeopardising the peace and security of the country”.

It added that the Council of Ministers discussed the damage by the protests across the country and declared the state of emergency in a message delivered to Hailemariam.

Al Jazeera’s Fahmida Miller, reporting from Mombasa, said that people were concerned about “the powers this state of emergency allows the prime minister to have”.

“The security forces for example will now fall under the prime minister’s control specifically. And if we look back over the last year, things like the internet have been blocked to prevent people communicating and allowing these protests to continue,” she said.

Protests reignited this week in the Oromia region – the main focus of a recent wave of demonstrations – after dozens of people were killed in a stampede on October 2, which was sparked by police firing tear gas and warning shots at a huge crowd of protesters attending a religious festival.

The official death toll given by the government was 55, though opposition activists and rights groups said they believe more than 100 people died as they fled security forces, falling into ditches that dotted the area.

According to government officials, factories, company premises and vehicles were burned out completely or damaged during the recent wave of protests. Many roads leading to the capital, Addis Ababa, were reported to be blocked.

The death toll from unrest and clashes between police and demonstrators over the past year or more runs into several hundred, according to opposition and rights group estimates. At least 500 people have been killed by security forces since anti-government protests began in November, New York-based Human Rights Watch group said in August.

The government says such figures are inflated and has denied that violence from the security forces is systemic. In August, it rejected a United Nations request to send in observers, saying it alone was responsible for the security of its citizens.

The anti-government demonstrations started in November among the Oromo, Ethiopia’s biggest ethnic group, and later spread to the Amhara, the second most populous group.

Though they initially began over land rights, they later broadened into calls for more political, economic and cultural rights.

Both groups say that a multi-ethnic ruling coalition and the security forces are dominated by the Tigray ethnic group, which makes up only about 6 percent of the population.

The government, though, blames rebel groups and foreign-based dissidents for stoking the violence.

|

Source: Al Jazeera News And News Agencies