Ethiopia Travels: On a Spiritual High

Travel video about destination Ethiopia.

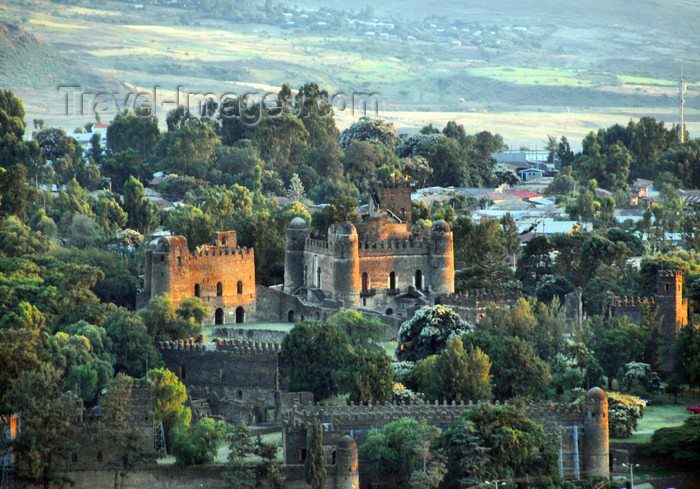

Ethiopia is a mysterious, mountainous land in the Horn Of Africa and birthplace of Early Christianity. A country of rock c hurches in the north and a large variety of tribes along the Rift Valley in the south and the oldest civilised region in Africa with more than twenty five centuries of documented history. Addis Abeba is the capital of Ethiopia and within its centre is the lavishly furnished Menbere Selassie Church, final place of rest of Ethiopia’s last royal family. It contains the Empress Menen, two princes and Emperor Haile Selassie who, shortly after removal from power, died due to reasons that are in the main controversial. On many of its thirty seven islands, Lake Tana in Northern Ethiopia is well known for its ancient churches and monasteries.

Ethiopia is a mysterious, mountainous land in the Horn Of Africa and birthplace of Early Christianity. A country of rock c hurches in the north and a large variety of tribes along the Rift Valley in the south and the oldest civilised region in Africa with more than twenty five centuries of documented history. Addis Abeba is the capital of Ethiopia and within its centre is the lavishly furnished Menbere Selassie Church, final place of rest of Ethiopia’s last royal family. It contains the Empress Menen, two princes and Emperor Haile Selassie who, shortly after removal from power, died due to reasons that are in the main controversial. On many of its thirty seven islands, Lake Tana in Northern Ethiopia is well known for its ancient churches and monasteries.

Dega Stefanos is located in the centre of the lake and contains one of the country’s most important monasteries. On the summit, framed by walls and hidden under great trees, is the Holy Stefanos Monastery and within a small sanctuary various mummies are preserved within glazed wooden coffins and the remains of five emperors of various dynasties lie at rest. Awash is a settlement on the edge of the nature park of the same name, inhabited by the Afar, a proud and independent tribe. On market day, people from the surrounding area meet here. For the Afar, life is hard and only the strong survive. Corn, tobacco, dates and cotton are the main trading products of this region. Dromedaries, sheep and goats are bred, and pastureland is often the subject of heated disputes. A journey through Ethiopia is also a journey through time itself. A land of rich traditions, religions and myths. A country of legends and contrast that possesses one of the most colourful histories on the African continent.

In Ethiopia’s remote northern highlands, hidden in the rock and rugged canyons of Tigrai, are some of the world’s oldest Christian churches. Travel to these soaring places of worship, carved with almost supernatural precision into mountains and sandstone cliffs, for an atmospheric insight into one of the world’s most unique religions.

There are just two at first, dressed in white, padding barefoot down the hill towards town. It’s dark, still a few hours before dawn and, as the tuk-tuk picks up pace, increasingly cold. Jacket pulled around my ears, the street ahead is just visible, filling with people fast: five here, 10 there, each clad in white; cotton shawls, long kemis dresses and thin sarongs. The road opens onto the town square and the tens become hundreds – and men, young and old, swaddled babies, sleepy-eyed children – all carrying skinny, wax-paper candles, illuminated faces turned towards a central podium.

Incense and incantations rise from the platform and ripple through the crowds. Tall-hatted priests, robed deacons and bearded monks recite prayers, returned by the congregation in a monotone echo, a mass of murmuring humanity glowing white against the night sky. That this nocturnal ceremony is conducted in Ge’ez, a language so ancient few speak or indeed understand it beyond religious litany, seems to matter not one bit. A priestly procession begins a slow, incense-trailing circuit around town, the faithful close behind.

Most travellers, even Africa-savvy ones, know little of Ethiopia. If associated with one thing, beyond the infamous famines of the 1980s, the country is perhaps best known for the striking collection of cross-shaped, subterranean rock churches found in the UNESCO town of Lalibela. But I’m not in Lalibela. I’m some 180 miles and several mountain passes away in the ancient capital of Axum. This tumbledown town barely registers on the international travel scene but is the very crucible of early Christianity in Africa and the holiest of destinations for Orthodox Ethiopians, who believe it’s home to the Ark of the Covenant.

The Ark — a chest containing the stone tablets on which the Old Testament’s Ten Commandments are carved — vanished from Israel in 587BC. Local lore suggests the sacred treasure materialised in Ethiopia in the company of Menelik I, a native royal who was supposedly the son of ancient Israel’s King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

Selassie & Solomon

Haile Selassie, Ethiopia’s final Emperor, is widely seen as the last in an uninterrupted 3,000-year Solomonic line. In the 1960s, his wife paid for the building of a new chapel in Axum to house the Ark — an artifact barely seen, much less verified, by anyone outside the church. But this ghostly relic is integral to Ethiopian faith, with every chapel, church or consecrated cave across the country containing an Ark replica. And occasionally, like tonight, they are taken out for a ritual airing.

Its procession complete, the velvet-clad chest returns to the church square on priestly shoulders and locals gather for blessings. Plastic bottles are proffered for holy water, along with jugs and giant jerry cans.

The holy men are not stingy with their benedictions. Some of the faithful approach the podium, wearing what appear to be eccentric Wise Men costumes — in fact, it’s the get-up of Ethiopian saint Gebre Menfes Kidus.

Despite common misconceptions, Ethiopia’s Orthodox Church is distinct and independent from the Coptic Christianity of Egypt out of which it grew. It does share some of Alexandria’s saints, albeit with Ethiopian makeovers. Inside Axum’s cathedral, I find a gallery of typical icons featuring saints with halos of Afro hair and wide, almond-shaped eyes. Christianity became the state religion in the fourth century, slowly merging with ancient Jewish and animist traditions. Its rituals — male circumcision, regular fasting days and an additional Saturday Sabbath — still reflect this unique genesis.

As the first blues of dawn fill the sky, the ceremony draws to a close. Women arrange herbs for sale on the roadside, fuel for the fires on which many will ceremonially brew coffee later. I go for a cuppa and a large slice of local history in Axum Museum. Brewed over fragrant coals in the courtyard cafe, the coffee is premium Ethiopian Arabica. The history is harder to digest. The emergence of Islam saw Ethiopia’s Christians largely isolated from the outside world until the 12th century. Reliable historical texts before this time are rare, and scholars are often at odds over key dates and details of early Ethiopian life.

The questions over dates are perhaps nowhere more fervent than in the dusty mountains around Axum. Here the landscape is littered with rock churches, soaring spaces of Christian worship sculpted with miraculous precision into sandstone cliffs and caves, some carved deep into the belly of the earth. Just how and when they were built, few historians can agree. Most of the churches remain little seen, accessed only by hours of off-road driving or high-altitude hiking. And in the case of tabletop mountain monastery Debra Damo, amateur rock climbing that involves rickety winches and not insignificant faith in the almighty.

The rocky road

“This is the place!” says Mali. “Medhane Alem Adi Kasho: Tigrai’s oldest rock church.” I squint towards the indicated scrap of dirt road stretching beyond a small hamlet of conical huts. It seems unlikely. But with hundreds of miles under the wheel since we left Axum, I’ve learnt to trust Mali, a savvy MBA from Addis Ababa and guide with Ethiopian travel company, Dinknesh Tours. “The priest will be here,” he continues as if by way of explanation. “I called ahead.” Sure enough, a local boy called Kinfe appears roadside, mobile phone in hand, rheumy-eyed priest at a respectful arm’s length. We have the key.

Following this fleet-footed pair uphill, we come to a sandstone plateau where Medhane Alem seems to rise out of the cliff from which it’s been carved. Fronted by four vast columns, rounded windows and a whitewashed facade, it recalls a Tibetan mountaintop temple — an arresting site surrounded by nothing but blue skies and scrubby eucalyptus trees, lit with the highlands’ laser-like sun. The outer door opens into an airy cloister with vaulted, rough-hewn stone ceilings. The key is applied to a rudimentary hole in a cliff-face door, systematically wiggled and the lock swiftly released with a grin of showmanship from the priest.

Inside, it’s as black as night. Mali clicks on his torch revealing the ceiling arching above us with a cathedral’s symmetry and grandeur. It’s carpeted with intricate carvings of crosses in several styles: Greek, St Andrew’s, svastika. I breathe in sharply, the air musty, the wonder immense. Who built this thing? How was it carved into a mountain with such mathematical accuracy? When does it date from? Do people still actually come here to worship?

One of my questions is answered by a gentle snore rising from the corner. A couple of parishioners are snoozing on a stone ledge, waiting for one of the church’s regular masses. Mali does a deft job of answering the rest. “Imperfection in the stone columns, and the style of blind windows suggest the church’s origins are 10th century.” He smiles: “But of course local tradition suggests earlier — maybe fourth or before in some basic cave-like form.”

Just how the depth of bedrock was measured, the stone excavated and symmetrical carvings made are questions hovering over all of the country’s hundred-plus rock churches, lending them an air of mysticism veering towards the fantastical. Outside, as we pick our way down the hill, the priest points out hoof-shaped recesses in the rocky slope, either made by St George or Christ Himself depending on who you ask. This is the only sub-Saharan country with tangible links to ancient Mediterranean civilisations in Syria and Egypt and it’s a beguiling and discombobulating place for it.

Add to this a more recent history that involves European nations in pursuit of colonial rule, and Ethiopia’s cultural map is often surprisingly shaped. Driving several hours over unsealed roads to find an eco-lodge equipped with an espresso machine is one example. Ethiopia grows some of the world’s best coffee and a hangover from a short Italian occupation that ended in 1941 means Gaggia machines are common even in remote towns.

New-era Ethiopia

Gheralta Lodge, a perfect example of post-aid, entrepreneurial-era Ethiopia, is an elegant brick-and-thatch eco-retreat run by an Italian-Ethiopian couple. By national standards it’s conveniently located between Axum and Tigrai’s main clusters of rock churches but that still means a butt-numbing afternoon’s drive along winding mountain roads that suddenly lose interest in themselves and run to dust before picking up again miles later. “Chinese investment,” mutters Mali conspiratorially.

Gheralta Lodge, a perfect example of post-aid, entrepreneurial-era Ethiopia, is an elegant brick-and-thatch eco-retreat run by an Italian-Ethiopian couple. By national standards it’s conveniently located between Axum and Tigrai’s main clusters of rock churches but that still means a butt-numbing afternoon’s drive along winding mountain roads that suddenly lose interest in themselves and run to dust before picking up again miles later. “Chinese investment,” mutters Mali conspiratorially.

I take a pre-dinner leg-stretch around the lodge’s rocky outcrops bulging over the Gheralta Escarpment with The Lion King-style drama. Across the valley, a distant horizon wobbles in the setting sun and I give into a hands-in-the-air ‘Hello, Africa’ moment, witnessed only by a couple of tall-eared hares loping around the gnarly roots of an enormous fig tree. Given Ethiopia’s vast size and varied terrain, eco-lodges are still few and far between but they’re fast multiplying. Most use their remote location as a selling point, with wilderness views, community-based tourism initiatives and wildlife treks in search of rare endemic fauna, such as the gelada monkey, Abyssinian lion and the Ethiopian wolf.

Gheralta’s staff are drawn from local villages, and it grows its own veggies, an amazing array of which — pumpkins, courgettes, beets, tomatoes among them — ends up on our dinner plate in the form of rustic Italian soups and tasty pastas. It makes a welcome change from the otherwise constant diet of injera. I like this fermented yeast-risen flatbread, or more specifically the thali-style selection of dishes that it’s dipped into. But it’s a taste any traveller to Ethiopia better acquire, so ubiquitous is this national dish.

Driving through Tigrai’s arid landscape — a biblical scene of long-horned cows with wooden yokes ploughing rocky fields — it’s hard to imagine much grows here. But it does. During wet season, Tigrai’s palate of browns blooms a jungly green, almost outshining the country’s verdant borderlands with Kenya. Stonewall terracing, elegantly criss-crossing the region, combats monsoon erosion and this, plus work for food programmes, means Tigrai has come a long way since the famines of the 1980s, now exporting grain, seeds, pulses and livestock across Africa and the Middle East.

En route to the rock church of Abreha we Atsbeha the following day, we pass its parish village, recently feted for no longer being reliant on food aid. High above it stands what’s considered to be Tigrai’s finest rock-hewn church, its square front cut boldly from the surrounding towers of sandstone. The perfect cruciform interior burrows 42ft deep into the mountainside; 20ft-high carved ceilings supported by 13 pillars.

It’s a jaw-dropping triumph of excavation, especially considering it supposedly took place in AD335. But I’m utterly seduced by the crumbling, chirruping atmosphere of Wukro Cherkos. At this nearby rock church, a celestial chorus welcomes us. The vaulted ceiling is twittering with barbets and starlings, and rich with geometric patterns. Above us, visible through weatherworn walls: canyons, mountains and big sky. Where you might stifle a yawn in a European cathedral, no matter how majestic, Tigrai’s churches, seemingly organic edifices, are magical, meditative places to be; seamless parts of the landscape itself.

Outside, the calm is broken by the clamour of the children at their prayers. Church schools are still an integral part of life here, and not only in deprived rural regions where state education may be scant but across Ethiopia. “If you want to become a doctor or lawyer, go to a church school,” grins Mali. “Learning hundreds of prayers in Ge’ez really teaches you to memorise well.”

The final pilgrimage

Teetering on the edge of a rocky escarpment some 8,500ft above sea level, Lalibela has a theatrical setting, its dirt streets heavy with the sounds and scents of mass, and the ever-present bustle of traders, beggars and bleating livestock. And then there are the churches. These UNESCO-enshrined, monolithic marvels are set deep into the ground, many cut in perfect cross shapes, entirely free from the surrounding rock on three or four sides. Looking down on Bet Giyorgis church, Lalibela’s cruciform masterpiece first appears oddly two-dimensional, a strange tattoo in the earth, its depths so hard to fathom.

A white-robed priest steps out of the shadows below, bringing a human dimension to the enormity. We follow a winding flight of subterranean stone steps, polished slippery by thousands of pilgrims’ feet, into the trench around the church. Now, with a trained eye, I can see Axumite influences everywhere. But the carvings, icons and frescoes lining the ceilings, pillars and walls have a unique finesse, the culmination of centuries of craftsmanship.

In sharp contrast, the surrounding trench walls are cracked, weathered and pockmarked with abandoned hermits’ caves and graves, some scattered ghoulishly with femurs and skulls. I surprise myself with a shiver. The air is dank but the comforting murmur of mass confirms Bet Giyorgis to be no monument to a dead religion. Buried in the earth they may be, but I’ve rarely found anywhere so strangely, geologically, spiritually alive as Ethiopia’s rock churches.

ESSENTIALS Ethiopia

Getting there

Ethiopian Airlines operates the only direct flights from the UK to Ethiopia, between Heathrow and Addis Ababa.ethiopianairlines.com

Average flight time: 8h50m.

Getting around

Vast distances separate Ethiopian destinations, so internal flights are essential. Ethiopian Airlines has daily services connecting Addis to most destinations. Driving between destinations is possible but not for the faint-hearted. Car hire usually comes with a driver but costs around £100 a day. Booking onto a group tour is more economical. Local handler Dinknesh offers itineraries across the country (dinkneshethiopiatour.com). The bus network is good, but distances are great and travel is slow. Taxis and Bajaj (auto-rickshaws) are plentiful in cities. Paying a higher price than locals is normal.

When to go

Ethiopia has a mild climate with the highlands averaging 20-25C year round. Pack a jumper for evenings. Southern and eastern lowlands can be sweltering. Monsoon season is June-September.

Source: natgeotraveller