Some Durham ministers challenge the image of traditional “White” Christ

“You shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free,” preaches the Rev. Curtis Gatewood to the 25 people crammed into the small red building on Carroll Street in Durham’s West End. Formerly a residence, the one-story property was converted into an anti-violence museum two years ago in an attempt to combat the drugs and violence that plagued the surrounding community.

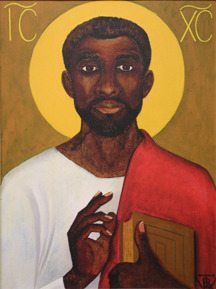

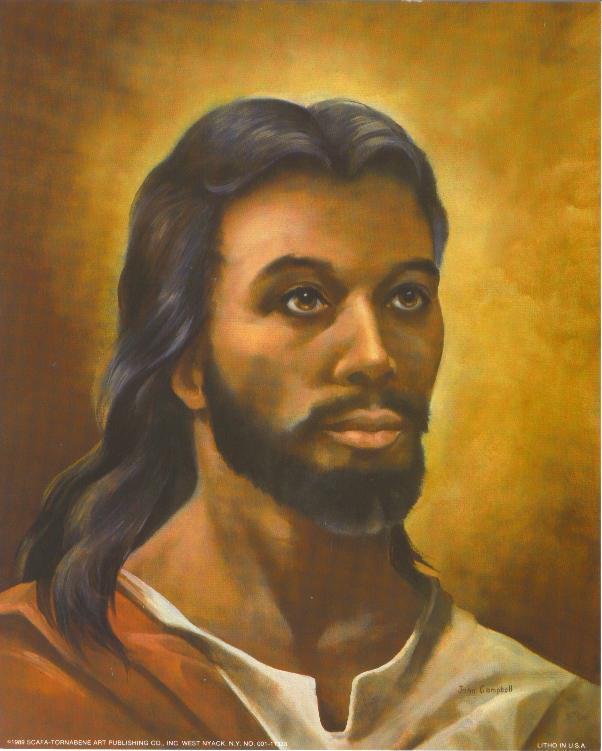

At present, no one is there to view its exhibits. For today, like every Sunday, the museum has been transformed again–into a church. It’s a church where the word “truth” flies about at least as often as such religious standards as “hallelujah” and “amen.” A church where the vast majority of the referenced biblical figures, including the Messiah himself, are as black as its members.

“If history and scripture point to Jesus as being a person of African descent, then it would be against God to represent anything other than this truth reveals,” says Gatewood. As leader of the New Day Christian Revolution, an “action-oriented” group that recruits door-to-door and through flyer distribution, Gatewood is committed to “doing God’s will by representing truth unbound.” An important part of this commitment is its challenge to the “white supremacy of the traditional church” and its creation of “false images to make things consistent with Eurocentric theology.” Gatewood refers to the popular images of a blond, blue-eyed Jesus constructed by European Renaissance painters and, more recently, by way of the 54-year-old oil painting entitled “Head of Christ” by Warner Sallman.

“The black church has been put in the box of Westernized theology,” he insists, saying that his movement “is in the process of breaking such boxes down. We are not willing to compromise truth for the sake of a brainwashed Christianity.”

Gatewood is not the only Durhamite breaking down Western religious belief and its constructed images of Jesus.

“The theology used to enslave and persecute you on Friday can’t be the same one to uplift and resurrect you on Sunday,” says the Rev. Paul Scott, head of the New Righteous Movement. This past May, the dozen-member organization waged an internet-based campaign against CBS’ airing of a miniseries that featured a white Jesus. It instructed people to call, e-mail or write the network to “demand Afrocentric images of the Messiah” and let CBS know that “we are tired of the lies.”

Scott points to the biblical descriptions of Jesus as having “hair like wool” and “feet like bronze” as partial evidence of his African origins. He, like a number of others, also considers the “so-called Middle East” as a part of Africa only “recently divided by the man-made Suez Canal,” and therefore inclusive of Jesus’ birthplace.

Along with the Internet, Scott has used street-based campaigns and gospel radio to push what he terms as his “Afrikan liberation theology.” Although he has been a guest on stations in Greensboro and in other states, Scott is quick to point out that a number of gospel stations in the Triangle have made it clear that his message is not wanted. On one occasion, after attempting to call in and offer his views, he was informed by a screener that he couldn’t discuss such topics because it “might offend our white listeners.”

Scott attributes such occurrences to a widespread “fear of a black Jesus. Many whites whose kids have Shaq posters on their walls and listen to DMX CD’s are scared their little ones will start walking around sporting black Jesus T-shirts.”

Scott and Gatewood both recognize that such portrayals of a black Messiah are far from new. In America, the portrayal of Jesus as a person of color dates back at least to the late 19th century. During the violent aftermath of Reconstruction, Henry McNeal Turner, a pioneering bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, would commonly declare that “God is a Negro” while informing his congregation to reject everything the white church taught about black inferiority.

In the first part of the 20th century, Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association continued this tradition as part of the African Orthodox Church. A half-century later, similar themes and images would surface during the civil rights and black power movements in the form of critical attacks on white Christianity by the likes of Malcolm X and James Cone. Cone, the founder of “black liberation theology”–an effort by American blacks to claim both their heritage and their freedom as a people of God–would boldly write in a 1969 book on the subject that “Christianity is not alien to Black power, it is Black power.”

And some countries in Eastern Europe have long-standing traditions of black Madonnas, like the patron of Solidarity promoted during the Polish worker uprisings of the 1980s.

“The fact that Jesus was African is one that is historically and unequivocally conclusive for anyone looking at it from an objective perspective,” says the Rev. Herbert Eaton, a former assistant dean at the Howard University School of Divinity. In the 1970s, Eaton, who holds a master’s degree in African history, was awarded several grants to study African religion and history at Harvard University, Howard University and the University of Ghana. The retired Durham resident currently offers his considerable experience to a course he teaches on biblical anthropology each week at First Calvary Baptist Church.

“The people who inhabited that area of northern Africa long before the building of the Suez Canal were obviously African,” continues Eaton. “His ethnicity was Hebrew, and he was raised under the religious system of Judaism. This is who he was.”

But if this, in fact, is who he was, why is it important? And what implications does it have for people today?

Pastor Carl Kenney of Orange Grove Missionary Baptist Church feels this “more historically accurate image is essential for developing good self-esteem among African-Americans.”

According to a study conducted by Duke religion and culture professor, the late C. Eric Lincoln, many African-American church leaders agree with Kenney. As co-author of the book, The Black Church and the African-American Experience, Lincoln polled 1,765 black clergy from various denominations around the country on whether or not it is important to have black figures represented in Sunday school literature. Sixty-eight percent–1,215 clergy–responded affirmatively, with a substantial segment of them offering justifications similar to Kenney’s.

However, of the 32 percent who responded negatively, the majority of them felt, as one minister suggested, that “skin color is of no great significance in relating the message of Jesus.”

Eaton disagrees, suggesting that such knowledge of the strong African presence in biblical history can bring about a healing. For thousands of years, he continues, “foreign and religious influences have negatively impacted our African communities, our religious life, our souls and our theological orientations.” Through teaching African and biblical history and encouraging a better knowledge of self, Eaton focuses on “trying to heal that brokenness.”

For some, the implications go beyond the black community.

“The test of equality is not whether you can accept black people sitting at the same lunch counter or living in the same neighborhood as you,” offers Scott. “The true test of equality is whether or not you can accept my Afrikan, dread-locked image of Jesus.”

Source: IndyWeek