Delving into Ethiopia’s ancient past and present

I’m edging my way through a long tunnel in pitch darkness, feeling for the roof so I don’t hit my head, waving my trusty flashlight around to scan the walls and sandy floor and check for any unwelcome wildlife. I feel like Indiana Jones but a lot less brave.

Then, after rounding a bend, I see a dot of light and emerge into a small cave. Through two large holes in the wall, I glimpse a splendidly carved building — one of the famous rock-hewn Lalibela churches. But when I peek through the holes, I see that they are halfway up a cliff face with no visible way down — no steps, no handholds … and it’s way too far to jump. So, behind me is the pitch-black tunnel I’ve just come out of; ahead a vertiginous drop.

Just for a moment I find myself wondering what on Earth I’m doing here. The answer is simple: I’ve been intrigued by Ethiopia ever since I heard stories about the Ark of the Covenant — a chest said to hold the biblical Ten Commandments inscribed on stone tablets — being here.

There are icons, castles, churches carved out of living rock, and one of the most ancient and vibrant forms of Christianity. Ethiopia is also said to have been the land of the Queen of Sheba and — as if that weren’t enough — of Prester John, whom fables in medieval Europe held to be the Christian ruler of a kingdom lost amid the Muslims and pagans in the Orient.

It’s obvious I had to experience Ethiopia for myself.

Admittedly I had some qualms before setting out. Everyone I asked, even intrepid young men, went on organized tours — while I would be a woman alone. People who had been there told me the capital, Addis Ababa, was overwhelming; those who hadn’t been there begged me to take care — or better, call it off.

In fact I began to wonder if I was completely mad. But tours are just not my style. I’ve always traveled on my own; I feel it’s the only way to truly experience a country and meet the people; added to which, guidebooks and friends of friends who’d been there assured me that Ethiopia is very safe — the safest country in Africa, no less. The only dangers might be having my pocket picked or getting food poisoning, both of which I felt prepared to deal with (and neither of which befell me).

Ethiopia is one of the poorest countries in the world, known for the famine that devastated it in 1984. It borders on Somalia and was wracked by a two-year war from 1998-2000 over a border dispute with Eritrea. But while not wealthy, I was to discover the country is peaceful and orderly, with very friendly people.

At the airport, instead of scowling as most immigration officers do, the official gives me a huge smile and says, “Welcome!”

Addis Ababa, which is home to around 2.5 million of the country’s roughly 87 million population, has a rather elegant Mediterranean feel, with houses washed in pale colors and trees rising between them. Mountains loom not far away, pale and misty. The streets are dusty. There are cranes and bulldozers, new roads being dug, buildings going up. This is a city in the process of making.

The people look sophisticated and well-dressed. Women wear their hair plaited tight to the head then flaring out at the shoulders. They are black-skinned with straight noses and huge eyes, very beautiful.

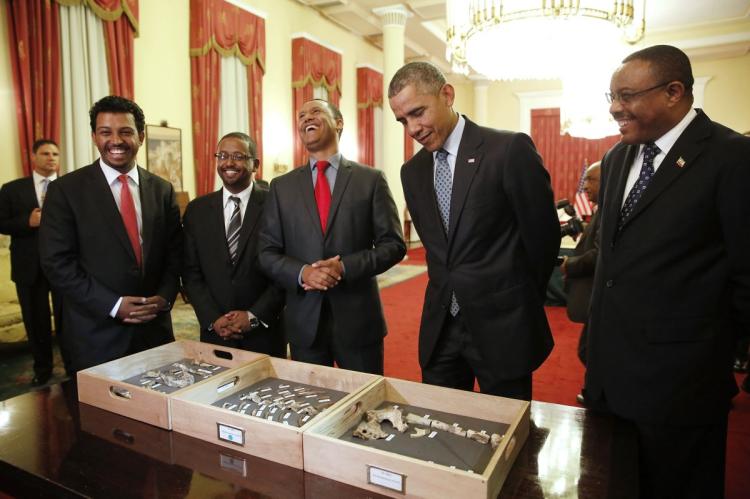

I start by paying my respects to Lucy. Some 3.2 million years ago, Lucy walked upright here amid vegetation very different from today’s. One of a species of hominid known as Australopithecus afarensis, she is among our most ancient ancestors — a missing link connecting us to the apes.

Parts of Lucy’s fossilized skeleton and skull were discovered in Ethiopia’s Awash Valley, some 110 km from Addis, in 1974, and are now in the dimly-lit basement of the city’s National Museum. It’s curiously moving to see her bones alongside the skull of a 3-year-old girl with a small, pointed, pixie face who lived even earlier, 3.3 million years ago. I feel as if I’m reaching back to touch the origins of humanity.

At the museum’s Lucy Restaurant, airy and tropical with outdoor tables under palm trees, I have my first taste of the Ethiopian staple, injera — a grayish-brown fermented bread like a huge chapati with a sourdough taste. It’s usually served with meat but I order “fasting food,” the vegetarian meal that devout Ethiopians eat for three months before Easter. Piled on the injera are different sorts of spicy dal — brown, orange, green — together with a whole chilli and piles of spinach and carrots. In proper Ethiopian style I tear off pieces of the bread, wrap dal and vegetables in it, and pop the lot into my mouth.

Early next morning I fly to Aksum, in the north of the country. In ancient times Aksum was the capital of a mighty empire, as glorious as Greece or Rome, which flourished between the third and sixth centuries A.D. and dominated the area between southern Arabia and the Sudan. Here merchants from Egypt, Arabia and India met to trade in gold, frankincense, rhino horn, apes and ivory.

In Addis I hired a car and a driver. But now the time has come, I decide, to step out alone into the dusty streets. For the first few minutes I feel a little apprehensive, but then I look around and realize I have nothing to fear. While older people are dignified and go about their business and pay no attention to me at all, the youngsters seem extremely friendly. Many speak excellent English and are eager to practice it.

These days, Aksum is little more than a village, but it’s dotted with obelisks soaring into the sky or lying in fragments on the ground, mysterious remnants of that ancient empire. The largest cluster of these stelae is at the end of the valley, where they rise like great stone needles out of the dusty plain, carved with ornamental windows and doors like ancient skyscrapers. Beneath them are a network of ancient carved tombs, chamber after chamber disappearing into darkness.

The most splendid stele of all, carved with a hammerhead top, has only recently returned here. In 1937, during the country’s 1935-41 occupation by fascist Italy, it was shipped to Rome on dictator Benito Mussolini’s orders and erected in the Piazza di Porta Capena. After lengthy negotiations, it was only brought back in 2008.

Ethiopia and Italy share a bitter history. Unlike virtually every other African country, Ethiopia was never colonized, but it was invaded by Italy several times. My visit coincides with the anniversary of the Battle of Adwa on March 1, 1896, when the Ethiopian army defeated the Italians — one of the very few non-Western countries ever to have trounced a Western one. The day is a national holiday and everyone I meet proudly tells me the story of how the Ethiopians sent the Italians packing.

For me, as a long-time devotee of Japan, there’s something familiar about the fierce independence of this country, one of the few non-Western nations to avoid the yoke of colonization, and one that maintains its proud culture intact.

In the museum at Aksum there’s fourth-century pottery, carved ivory, glass goblets, coins and beautiful painted icons. An elderly curator shows me a rock inscribed with ancient writing, then starts reading out loud, tracing the words with a gnarled finger. The first line reads from left to right, the next from right to left, and the letters too face one way then the other. The language is Sabaean, the precursor of Amharic, the modern-day Ethiopian script — for, long before the Aksum Empire, this was Saba — aka Sheba. Though there’s no firm historical evidence, Ethiopians believe that Aksum was the Queen of Sheba’s capital.

But Aksum is far from being just ancient ruins. It’s the home of the Ark of the Covenant, the heart of the Ethiopian church.

Across the road from the stelae is the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian cathedral of St. Mary of Zion, the Virgin Mary, where the Ark is supposedly housed. Pilgrims swathed in scarves and shawls press their foreheads to the wall of the compound and kiss it. In the grounds men, tall and dignified with beards and turbans, carrying fly whisks and praying sticks, face the entrance to the cathedral and bow. (They pray standing up, sometimes for hours, and use the sticks to rest on.)

The cathedral is domed like a Russian Orthodox church. (The original cathedral is being renovated and this is a modern one built by Emperor Haile Selassie [1892-1975]in the 1960s.) It’s full of beautiful icons, some showing a black Virgin Mary and Christ. One, from the 16th century, depicts Emperor Menelik, the son of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, on his way back to Ethiopia, walking through a landscape of palm trees accompanied by a retinue of robed, bearded men. One is bearing on his head an ornate casket: the Ark of the Covenant.

And there in the grounds is the chapel where the Ark is said to be. It’s a modest building, newly rebuilt, of gray stone, with blue-framed windows.

“Can I see the Ark?” I ask the deacon, a handsome man who, like many people here, speaks excellent English. I know the answer, but there’s no harm trying.

“No one sees it,” he says. “Not even we may see it. The only one who sees it is the custodian.”

As for the custodian, the deacon says he has never seen him either, as he never leaves the chapel.

It’s a mystery worthy of Dan Brown’s 2003 thriller, “The Da Vinci Code.” Of course, the Ark would lose its mystique if it were on view for everyone to see. But every church in Ethiopia has a model of it, called a tabot, hidden away in the inner sanctum.

In the streets outside, people robed like Old Testament figures herd flocks of sheep. Donkeys and camels amble by, oblivious to the crumbling ruins. Little blue three-wheeled tuk-tuks buzz around, their drivers eagerly touting for business as they churn up clouds of dust.

There are stelae and ruins everywhere around the town, evoking that ancient civilization centered here, once so grand and with the resources and energy to create these obelisks, yet now utterly vanished. Women wash their clothes in the so-called Queen of Sheba’s Bath, a huge lake of brown water, and I visit a mazelike ruin known as the Queen of Sheba’s Palace, with a brick oven and neatly fitted paving stones that floored what might have been the throne room. Cocks crow, donkeys bray, cows moo.

As I walk back through town in the cool of the evening I meet Samuel, aged 13, a round-faced solemn lad. He is on his way home from school in his purple uniform and shows me his maths and English homework. Everyone is busy. Children kick balls, people play table football, women weave baskets. In the shade men work treadle sewing machines while camels laden with firewood stretch their necks and snort disdainfully.

I spot a woman in a rather beautiful black blouse sitting with a tray full of cups against a tree with a leafy roof over her head. So I decide to stop for a coffee ceremony and take my place without a moment’s hesitation. Men sitting there, sipping coffee, ask if I am from Italy. When I say, “No, England,” they shout, “Good, good.” One tells me that he supports Manchester United, another is an Arsenal fan. A conversation about football ensues, so esoteric that I am hard put to keep up with it.

Some days later I set off for Lalibela. It’s 260 km to the south, back towards Addis — a quick hop by plane or a long day’s drive. The landscape is strikingly different from Aksum, with jagged mountains on the horizon and little round thatch-roofed houses, the same tawny pink as the soil.

In the hotel I’ve booked, I have my own round house, called a tukul, cunningly insulated with corrugated iron under the grass roof, and with an earthenware jug balanced upside down on the pinnacle. Inside it’s neat and clean, with tables, chairs, snow-white bed covers and a balcony offering a view of hills.

Lalibela is the home of those famed rock-hewn churches. Some time in the 12th century A.D., a saintly king named Lalibela decided to create a new Jerusalem, in both its physical and heavenly forms, here on Earth. According to legend, he was actually taken to heaven, where angels showed him a fabulous city of rock-hewn churches and commanded him to build a replica. There are 14 of these churches in Lalibela, and even place names around here are Biblical: the Jordan River, Calvary and the Tomb of Adam, among others.

A steep road winds up the hill but I don’t see any churches. I soon discover why: It’s because they’re below the ground, cut into — or out of — the rock.

Ethiopian Orthodox Christians’ lives are saturated with their religion whether it’s paying homage to Lalibela, and the 11 churches carved into the ground or wearing respectful garb and praying before meals. Timket is a celebration that reflects on Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan River and lasts for three days towards the end of January.

I plod on up in the heat of the sun and cross a deep gully which my guidebook tells me is the Jordan River, then pay my entrance fee and clamber down a crevice in the rock. And there before me is a vast building, as big as a cathedral — it’s Bet Medhane Alem (bet means “saint”; medhane alem, “savior of the world”). It’s columned like Greek temples, but the columns are purely decorative, they don’t support the roof; and it’s beautifully carved so it seems to be made out of large stones laid one on top of the other, or layers of wood and stone. In fact, though, it’s a perfect illusion, because it’s actually carved directly out of the rock. As it’s surrounded by a walled courtyard, to be there is like standing at the bottom of a moat.

Inside the church, dim shafts of light beam through the window slots. I shine my flashlight around the frescoes and carvings on the walls. Dank carpets cover the stone floor and velvet drapes hide the inner sanctuary. The priest, dignified in white robes and a turban, shows me three hollows — graves prepared for Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Everything is symbolic, everything has a meaning. He brings an ornate iron cross out of the inner sanctum. An old man kneels and touches his head to the ground. Others sit in pools of light, poring over prayer books. There are drums lying around, to be beaten as part of a service. This is a holy place. Ethiopia’s Orthodox Christians — believed to number around 35 million, alongside 25 million Muslims and 14 million Protestants — come here to worship, not to sightsee.

At Lalibela, there are two groups of churches. All are carved out of beautiful volcanic rock, the color of the soil, the red earth of Africa, and each is different and unforgettable. The churches of the northwestern group are close to each other, but even so it’s like solving a riddle getting from one to the next. I climb through tunnels and over precarious rock bridges and occasionally scramble up a rock face. I look for the Tomb of Adam, marked in my guidebook, but I can’t find it.

The churches contain icons of the Virgin Mary and the Holy Trinity, and many also have paintings or reliefs of St. George and the Dragon, an important figure in Ethiopia’s Orthodox Christianity. Legend has it that when King Lalibela had completed 13 churches, St. George suddenly appeared to him in full armor, on horseback, demanding to know why there was no church for him.

I leave the last of the northwestern group of churches and walk past a village of tukuls, like little round gingerbread houses. Over the crest of a hill I see before me a huge cross, flat to the ground, beautifully carved, which seems almost to be floating, surrounded by empty space. As I walk closer I see that it’s the flat roof of a four-story church, dug deep into the ground — in fact it’s the most magnificent of them all, Bet Giyorgis, the Church of St. George, built on the saint’s command.

I walk down a long winding tunnel to gain entrance. Inside there is an ancient icon of St. George and the Dragon and two mysterious padlocked chests. Outside, dried feet and legs are visible in a cave in the wall, the mummified remains of Syrian pilgrims who wanted to spend the rest of eternity in this holy place. There are also curved hollows in the wall — hoof marks made by St. George’s horse. Everything is symbolic, everything has a meaning.

On my way back I stop to photograph a threadbare brown sheep that’s tearing at a bit of dry shrub. A woman runs over, waving her hands. “You like?” “Yes, I like,” I say politely. “Very cheap,” she says, and I realize she thinks I want to buy it. When I gesture “No,” she runs after me, repeating, “Very cheap.” I tell her that sadly I can’t fit a sheep in my suitcase.

The following day I set off to tackle the second, less accessible southeastern group of churches. As I scramble up the hillside, I see a woman stooped under a huge bundle of firewood tied to her back, pressing her head to the tree beside the bridge that leads to the churches and kissing it.

I cross a narrow stone bridge high above a deep moat to the first church, Bet Gabriel-Rufael, then look for the second one, Bet Merkorios. The ancient and rather surly custodian there points me on my way to the third and I plunge into a dark tunnel, with no idea where it leads or how long it goes on for. And so it is that I come to be hovering nervously in front of two large holes in a cave wall above a precipitous drop.

In the end, I decide I’ll just have to miss this most finely carved of all the churches, Bet Amanuel (St. Emanuel), which was reputedly the royal family’s private chapel. So I reluctantly retrace my steps back through the dark tunnel. As I’m leaving I pass a church custodian and a policeman, who call out to me that I’m going the wrong way. They laugh hugely when I tell them I was too afraid to climb down. It turns out there’s a long way round. The policeman leads me there.

It’s well worth it. Bet Amanuel is a beautiful church, exquisitely carved, with windows featuring fretwork crosses and inset doors. Inside is a gorgeous icon of the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus, dark-skinned with huge dark eyes and haloes that glow like suns. The priest here has a particularly finely wrought cast-iron cross adorned with purple and gold scarves.

I look for the hole high on the cliff where I had stood, too afraid to climb down. Now I can see shallow steps but still no hand holds. I’m glad I came the long way round.

After the peace and quiet of Aksum and Lalibela and the slow pace of village life, it’s a shock to be back in the hurly-burly of Addis Ababa. It’s a big dusty city with a shopping center and, strung out along the roads, open stalls selling covetable handicrafts — icons, bracelets, shields — and there’s a well-developed area near the airport with glamorous stores, a spa and air-conditioned restaurants where I feel I could almost be back in Tokyo.

I visit the Ethnological Museum, which has displays of tribal customs and a wonderful collection of historical icons. The exhibits are fascinating but I’m intrigued by the splendid building itself, which was once the palace of Haile Selassie — who was formally known as His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, King of Kings of Ethiopia, Elect of God.

Above the glass cases, the Throne Room has yellow and white colonnaded walls and chandeliers. In Haile Selassie’s bedroom there is a huge bed with a blue velvet canopy and photographs of the bearded monarch, straight and proud with his chest covered in medals, and a bronze statue of the Lion of Judah, as befitted the heir to a dynasty that traced its origins by tradition from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. The mirror has a bullet hole in it, the aftermath of a failed coup d’état. It was Haile Selassie’s good fortune to be out of the country at the time.

Unexpectedly, it occurs to me yet again, there are aspects of Ethiopia that remind me of Japan — its long history, proud people who were never colonized and the uniqueness of its culture. Until recently, it even had an emperor with a lineage stretching back to ancient times.

Brimming with history almost literally from the beginning of time, when Lucy walked the earth, with its heat and dust, sunshine and palm trees, its stories of Solomon, the Queen of Sheba and the Ark of the Covenant, and possibly the oldest ongoing Christian church in the world, Ethiopia is endlessly fascinating. My only caution to visitors would be: Don’t forget your flashlight.